Death Gate was a single-player, fantasy, graphic adventure game (in the classic sense of using verbs and nouns to solve puzzles) for the PC based on the popular Death Gate Cycle series of books by Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman.

This is the story of its making.

The Property

Death Gate was one of many Legend games based on literary licenses. After original titles like the Spellcasting series and Timequest, we found that literary licenses were useful in a number of ways: they attracted the attention of publishers, they brought an existing audience with them, and–my favorite–they allowed us designers to putter around in worlds of which we were fans.

My first contribution to design in this endeavor was Frederik Pohl’s Gateway, followed by Gateway II. After that, I began to voice my own opinions about what licenses we should pursue. While I loved science fiction, I desperately wanted to make a fantasy game, so I suggested two licenses to chase: Piers Anthony’s Xanth and Weis and Hickman’s Death Gate Cycle.

Legend managed to get both. While Xanth was a popular title, it was more pun-based than I was comfortable with. In retrospect, it would have been a fun game to make, but I had my sights set on the darker and fascinating Death Gate.

I had been a fan of Weis and Hickman’s work ever since Dragonlance consumed what spare time I had between running Sundog Systems and doing CompSci homework at Penn State University. The authors constructed deep and interesting worlds and populated them with compelling characters. Since Dragonlance already had a boatload of games based on it through TSR (the makers of Dungeons and Dragons), Death Gate seemed like a perfect alternative.

Death Gate was more current, it was a self-contained series with a different publisher, and its world and premise lent themselves to an adventure game structure. And I loved it! It didn’t hurt that the authors were also excited about making a game. Margaret Weis in particular was approachable and ready to help. I remember her telling me that, if there was something I needed to know, and it would be faster and easier to call her and ask, I should do so. And I did!

The Design

How Many Books Are There Again?

Even though I had co-designed two games before this, Death Gate represented my first solo project. I was a young, headstrong designer who wanted to prove I could do it all: design, write, produce, art-direct, compose music, voice-direct, and even code it. I couldn’t do it all (I worked with a very talented team), but I about killed myself trying.

Here’s was my problem concerning the design (which became an issue on Wheel of Time too): I was a fan of the Death Gate series–at least, everything I’d read up until that point–but at the time, they weren’t done writing it. As a fan, I wanted to give other fans what I felt they wanted too. I wanted to tell the big story. I wanted to visit all the worlds. I wanted to meet all the characters. And I wanted a satisfying end.

How could one game do all that? Cover multiple books worth of material? And wrap it all up in a bow that hadn’t been written yet?

Even other designers at Legend were somewhat mystified with my intentions. My boss Mike Verdu looked at me strangely when I said I wanted to call the game ‘Death Gate.’ He asked, “Why not Dragon Wing? That’s the first book, right?” I just shook my head. He didn’t understand the awesomeness of what I had planned, and it took him a long time to come on board (he did eventually, when he saw the whole design).

I took a page from my efforts on Gateway I and II; Death Gate wasn’t going to be a literal translation of the books into computer game form. Instead, I translated the spirit of the books, with many of the main characters, places, and themes drawn from the original. I consolidated a lot and focused on the important bits that I needed to tell this story, which wasn’t quite the same as the original.

But, to design an adventure game adaptation, you have to make big changes anyway, right? Books aren’t written with adventure game structures and puzzles in mind. And even if that were true, how fun would it have been to play a game where the novels could act as hint books? Instead, the game had to be a new experience that fans would hopefully connect to because of their familiarity with the original books. I took a big chance by cutting out some fan favorite characters like Alfred, or making the dog companion into a later element, but I paid off on enough familiar material that I believe fans were happy with the end result.

It’s Just Logical

I’ve seen feedback that some players found Death Gate’s puzzles to be easier than some other adventure games. I contend that the puzzles aren’t necessarily easier; they’re just fair. They’re designed to be logical and supported by context. This was very important to me during the design phase, because I’d seen the alternative.

Excuse me while I go off on a designer rant.

Just before I designed Death Gate, I played a game called Dragon Lore from Cryo Interactive. It was ostensibly an adventure game with some combat elements. I played it solely to be aware of our competition.

While some of our contemporaries were producing some quality games (like LucasArts), this wasn’t one of them. The puzzles were horrible, illogical, and unfair. I can honestly say that this is the only game I’ve ever actually removed the disk from the computer’s drive and thrown it at the wall–just after I found out that the solution to a puzzle I was stuck on for the longest time had nothing to do with logic.

It wasn’t even a restore puzzle (something I teach my students to avoid; a restore puzzle requires the player to die in order to learn the solution and then restore to a point where he can apply the knowledge–Sierra’s games had a number of those). It was a walkthru puzzle, requiring a solution you’d never guess from the clues at your disposal in the game. Ever.

Every puzzle solution should provide an ‘Aha!’ moment, where either you feel smart for having figured it out, or you discover the answer elsewhere and smack your head for NOT figuring it out. If you don’t have enough information in the game to figure out the solution logically, you never get that moment. In an adventure game, that moment is the fun!

Another thing I tell my students is that the game designer is there to craft a satisfying experience for the player. The design isn’t intended to torment you or to ‘beat’ you (the designer isn’t even there to enjoy besting the player, so it’s not a satisfying goal to begin with). My philosophy has always been that a player puts his trust the designer to take care of him. Once the player has lost that trust, he’ll give up. Dragon Lore broke my trust. That’s why I chucked the disk. I wasn’t about to give the designer any more chances to mess with me.

OK. Rant over. You can tune back in.

What in the Worlds?

I designed Death Gate from beginning to end before we ever coded anything. That was hard. In previous games, working with talented coders, artists, and musicians to bring my designs to life was very motivating. And this wasn’t a collaboration; I was responsible for the whole thing. It was the biggest design challenge of my career (up until then): to blueprint a game from beginning to end. It required a couple of lonely months where I would go away and think, and then periodically dump my design to Bob Bates (co-studio head) to get feedback.

Arianus. This world went fine. I was happy with how the puzzles in the three areas worked together. I enjoyed writing the Dwarves’ dialog. I was especially proud of the chore to get the merchant’s amulet as proof of his death (making his first words to his betrothed ‘How Much?’ was a joke probably only I enjoyed).

Pryan. This world was harder. I felt more pressure to make progress, but when I finished the second section (getting the crystal piece in the dwarves’ forest), I realized that it was trash. I threw it all away and started again. That’s another thing I teach: when to cut bait and start over. The second pass became what’s in there now (much better). That said, I loved writing Zifnab’s dialog from the beginning; it was one of the most enjoyable parts of designing this game.

Abarrach. Designing non-stop takes a mental toll. When it was time to design this world, I so wanted to turn off my brain for a while. At this point, I was only half-way through all the worlds, and I wondered if I could really power through to the end. But when you try to stop thinking, you do the opposite. Soon, I started figuring out how to use the dead in clever ways to solve puzzles, and that energized me to keep going.

Chelestra. Ever wondered why Chelestra is so much smaller than the other worlds? That’s because when I reached this part of the design, I was suddenly given a room budget. I guess my overall design was getting big, and too many rooms would equal more art, more music, more time, and more money. A Chelestra as big as the other worlds would have taken too long to produce. So, given that I wanted to keep some rooms in reserve to produce a real experience in the Labyrinth, I made Chelestra a short, dramatic stop to set up the finale. However, it did contain an important moment: the dog’s sacrifice for you. Some fans confided that it made them cry. While that wasn’t the intention, I confess it kind of got to me too.

The Labyrinth. I didn’t need the Labyrinth to be huge, but I demanded a lot from its design. It was the culmination of everything before it. I wanted the puzzles, in particular, to ramp up. This is where designing everything up front had its upside: the player would leverage items, spells, and concepts from the entire game, not just that section.

The last puzzle, the one where the player must devine the correct starting rune of the interconnection spell and activate it, was hands-down the hardest in the game–intentionally. However, in retrospect, there were three major issues with it.

First, I violated my own rules of puzzle design; it was unfair, because it required that you remember one element of a conversation that was no longer available (the names of the six Sartan devils). In every other puzzle, you should be able to get the information you need to solve a puzzle, even repeatedly, at the moment when you’re trying to solve it.

Second, it required a number of complex steps (mini puzzles) in a limited number of turns before death arrived. That’s not actually the problem, however the difficulty made the alternative really attractive: just by brute forcing all six of the possible naming runes (by saving and restoring), the player could win and not understand why, which I consider bad design. By the way, the same was true of finding the antidote in Abarrach (too many people brute forced that puzzle as well, which is why I explained the actual solution in the text once the player had solved it).

Finally, you didn’t actually have to take the final book from Xar’s desk before you entered the Labyrinth. When I designed it, I couldn’t even contemplate the player NOT taking the book (I mean, Xar kept you from taking it the entire game, and now it’s just sitting there for the player to steal?) that I didn’t code in any safeguards to ensure it would happen. And once the player had entered the Vortex, there was no going back.

Still, I like the puzzle. It was a good finale. It just wasn’t perfect (dang it).

You got the High Score!

Sure you did. So did everyone!

To clear up any mystery, you may not have earned every point in the game, but I felt bad about cheating the player at the end. If you made your way all the way there, I thought you deserved the top score. Therefore, the number of points you won on the last move was 1500 minus your current score.

That’s how I cheated and was able to have the voice actor for Haplo tell you that you earned all 1500 out of 1500 points!

Players are competitive, but in Legend games, score wasn’t really about beating other people. I viewed it primarily as a tool to let the player know that their actions accomplished something significant and that they were making progress. So even if the resulting text wasn’t splashy, if you read ‘[You scored 15 points]’, you knew you were on the right track. That was way more useful than you might think, and definitely more important than a leaderboard for a single-player adventure game.

Let’s Make Magic

A big part of the game was the alternate interfaces: the screens that allowed the player to interact with the game in very different and specific ways that weren’t just about nouns and verbs.

Most of them were there to help pacing. They were intended to be significant moments that also gave a break to the player from the traditional verb and noun gameplay. I guess they were most like the alt-interface logic puzzles of games like Myst, but I only felt that they succeeded if they tied tightly into the traditional puzzles.

Three of these alternate interfaces served much more important functions: dialog, books, and magic.

In case you weren’t paying attention, I had a lot of story to tell and a small window in the main UI in which to fit the text. So I pushed all of that text into a CD’s worth of voiced dialog and a mountain of books. It was a lot, and if I wrote this game again, I’d probably edit it down quite a bit–but at the time, the audience of this game ate it up. It was exactly what they were looking for, and the voice and text fleshed out the world considerably.

The most important, and most useful of all of these, was the magic interface.

The rune-based magic introduced in the books was a fascinating concept, and I leveraged it into a unique magic system. The player could build his own spells with the collected runes, or choose from a list of spells already learned.

Each spell became its own verb, and boy did this make a mountain of work for me. One of the biggest challenges of an adventure game designer is making interesting (and hopefully funny) responses for all of the nonsensical actions the player can take. Now imagine adding a ton of new verbs you can apply to anything in the game, like Heat and Cold. What fun that was to think of hundreds of new responses spraying spells on every object in the game that likely few players would ever see.

That said, learning, building, and casting these spells was very satisfying, and magic was consistently one of the favorite features brought up by reviewers. It was a powerful tool for me as a designer, and I was happy about how it came together–especially when I got to use the runes themselves to make some interesting puzzles.

The Art

Legend had a few existing sources for high-quality art, including the talented artists at Kinetic Arts: Cindy Wentzell, Peter Calabria, Robert Wisnewski, John Carbone, and Tanya Isaacson. What’s more, Paul Mock had just come in-house to produce the 2D cutscenes.

But even with this crew, we were always looking for more. Legend simply had too many projects in the pipe and too few artists to feed them. If I wanted art for my game, I had to find it myself (working with a budget that you would laugh at if I told you).

I found a few new computer artists, including Anne-Marie Cox who did the in-room animations and made the mouths move on the character portraits (they weren’t synched to anything, but so many players swore they were). I also discovered a 3D artist to create the few 3D cutscenes (believe me, those Death Gate ship and Vortex shots were absolutely cutting edge at the time!).

But they weren’t enough. I had to look elsewhere. This wasn’t the first time I’d done this. In fact, on Gateway, I actually opened up the yellow pages and looked under Artist. One call I made was to Kathleen Bober, who still tells this story about how she entered the game industry. Kathleen painted some art for Gateway, but then started doing all sorts of other jobs, even helping me cast and produce the voice work for Death Gate.

Despite my small budget, I had high expectations for the art in Death Gate. This was intensified by the fact that Death Gate had the opportunity to be the first Legend game that used Super VGA. The increase in resolution was amazing. Suddenly, players weren’t squinting at a mass of pixels; they were enjoying art. I couldn’t waste this opportunity. I wanted it to look like every room was a piece of fantasy fine art like you’d find on any TSR cover or art book.

In that effort, I discovered David Cherry, a bonafide fantasy artist who’d never made game art before, but was willing to give it a shot. Like everyone else I spoke to, David didn’t work digitally, so he’d paint the scenes by hand, and we’d scan them in to use in the game. It made any changes very difficult. But it was worth it.

He was Such a Character

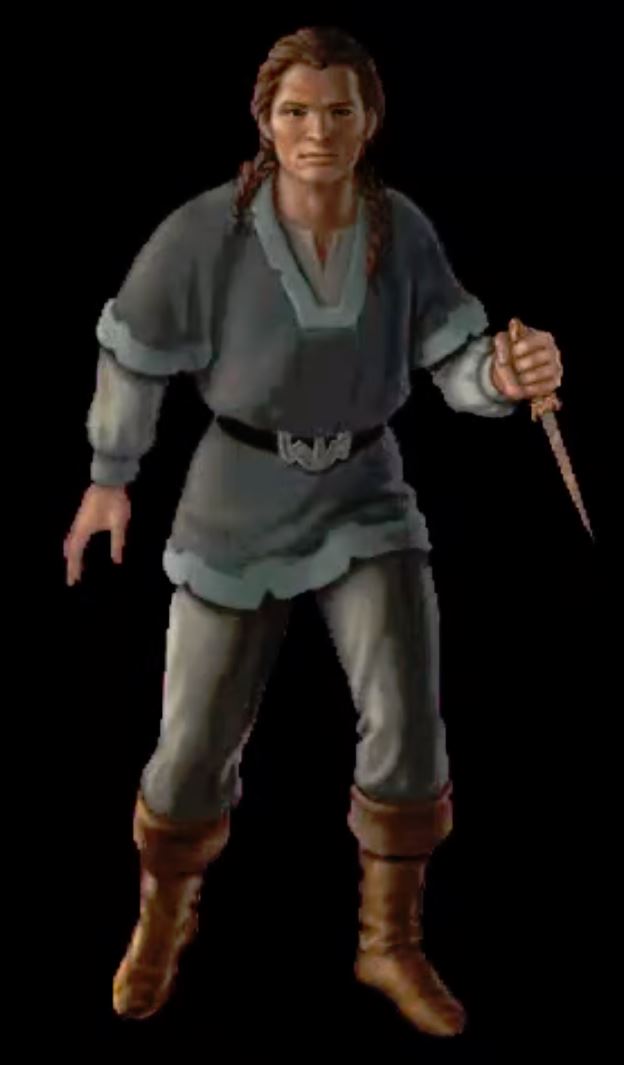

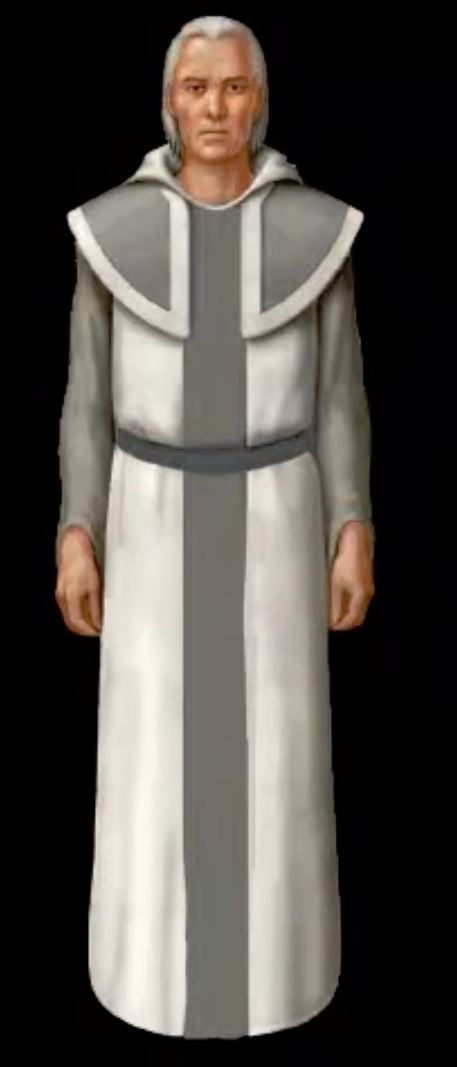

I discovered another local artist by the name of Fred Devita. Fred’s story, working for Legend, was one of the most heart-wrenching, yet personally moving tales I’ve experienced. Fred was a commercial artist who also worked on canvas. He had no idea what to expect, but was excited and motivated to make game art.

At first, Fred tried his hand at room art (the background art for each location), but for some reason, rooms took him an extraordinarily long time to produce. What’s more, the end result wasn’t always what I needed. Adventure game rooms have precise requirements, and even with detailed specs and pre-vis sketches, errors still crept in. Canvas corrections were time consuming and costly. What made this especially hard is that Legend paid based on finished rooms, not revisions. And, as a small adventure game developer, we didn’t pay well to begin with.

This was a path that would lead to ruin. Luckily, two things were about to change.

Fred was a trooper. He never complained and he soldiered on. But one day while talking over a new assignment, he let slip that he was planning on declaring bankruptcy, but continue to work through it. I was shocked. I couldn’t believe that working for us was about to drive someone to poverty.

I went to speak to Mike Verdu, my boss and co-studio head. When I explained that Fred was about to declare personal bankruptcy, he asked what we could do to keep that from happening. I explained, not expecting much, that we would need to double what we were paying him. Mike agreed without any hesitation.

It stunned me. I knew this solution wouldn’t fit in my budget, but Mike expanded it. He was willing to make the right call. I knew, in that moment, that was working for the right person at the right company. I raced to the phone. It was a wonderful moment to be able to tell Fred about the new arrangement.

Something else turned things around for Fred too. Normally, the artist who painted a room had to paint all of the elements that would appear in that room too. Those often included characters. On the first room Fred did this, I noticed something. The room wasn’t great, but the characters were so much better. You see, it wasn’t easy to find artists that rendered characters well, and Fred’s were better and more consistent than most of my other artists. I asked Fred if he would be willing to focus exclusively on characters and leave rooms to others–something we had never done before at Legend (or budgeted for, but it made too much sense not to go this way). Relieved with this direction, he agreed.

Rendering characters was right up Fred’s alley. He was much quicker, and the results were wonderful. I loved those characters so much that I displayed the credits with them, just so I could show them off in a bigger size. Here are some of Fred’s characters from those credits.

Side story: you probably didn't notice this, but the version of Xar in the credits did not match the version of Xar in the game. That's because Fred went behind my back to ask for a photo of me from my then-girlfriend so he could include me in the game somewhere. He used this reference to paint me as Xar. It was a total surprise to me when I saw my face on Xar. I wasn't excited about it, especially because the image wasn't as old as Xar was supposed to be, so I asked my animator to "old me up." But I decided to include the original in the credits. Fred also sneakily acquired a photo of my girlfriend as well and used her as a base for the human princess on Pryan.

After Death Gate, Fred had the opportunity to contribute to some of Legend’s other games, but his productivity slowed considerably. Later, I found out why. It turns out that, even when Fred was working on Death Gate, he discovered he had cancer–but never mentioned it to me at the time. Later, when he confided in me about his illness, he told me that, when creating those characters for Death Gate, he had discovered his life’s calling.

Fred died shortly thereafter. It was my first real exposure to death. At his memorial, I met lots of people from Fred’s life for the first time. In fact, I had only met Fred once or twice in person. They told me that he treasured our relationship. I did too. He was a friend. Of course, I’ll never forget him, but I’m also happy that his art in Death Gate will always remain as a testament to his talent.

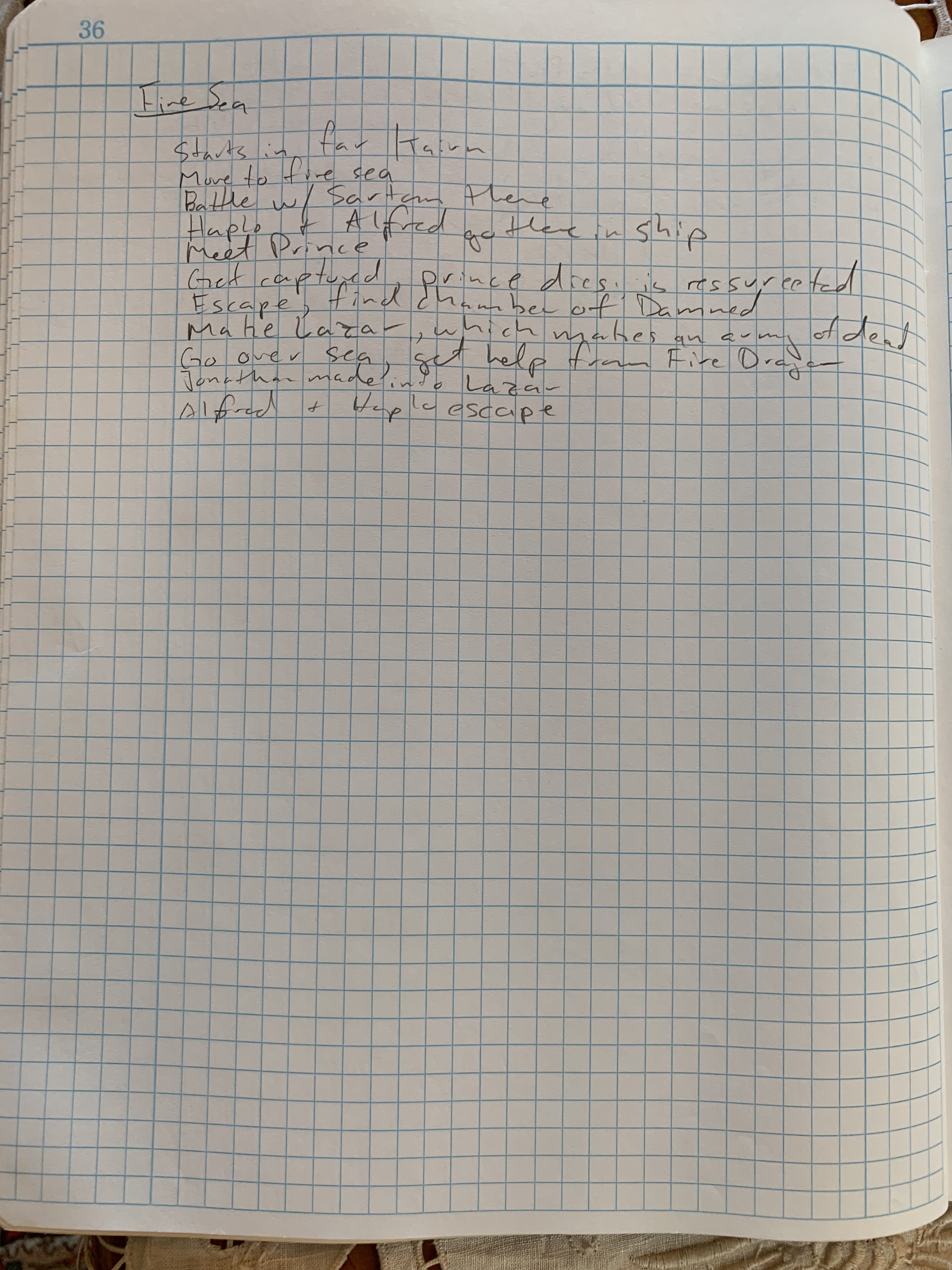

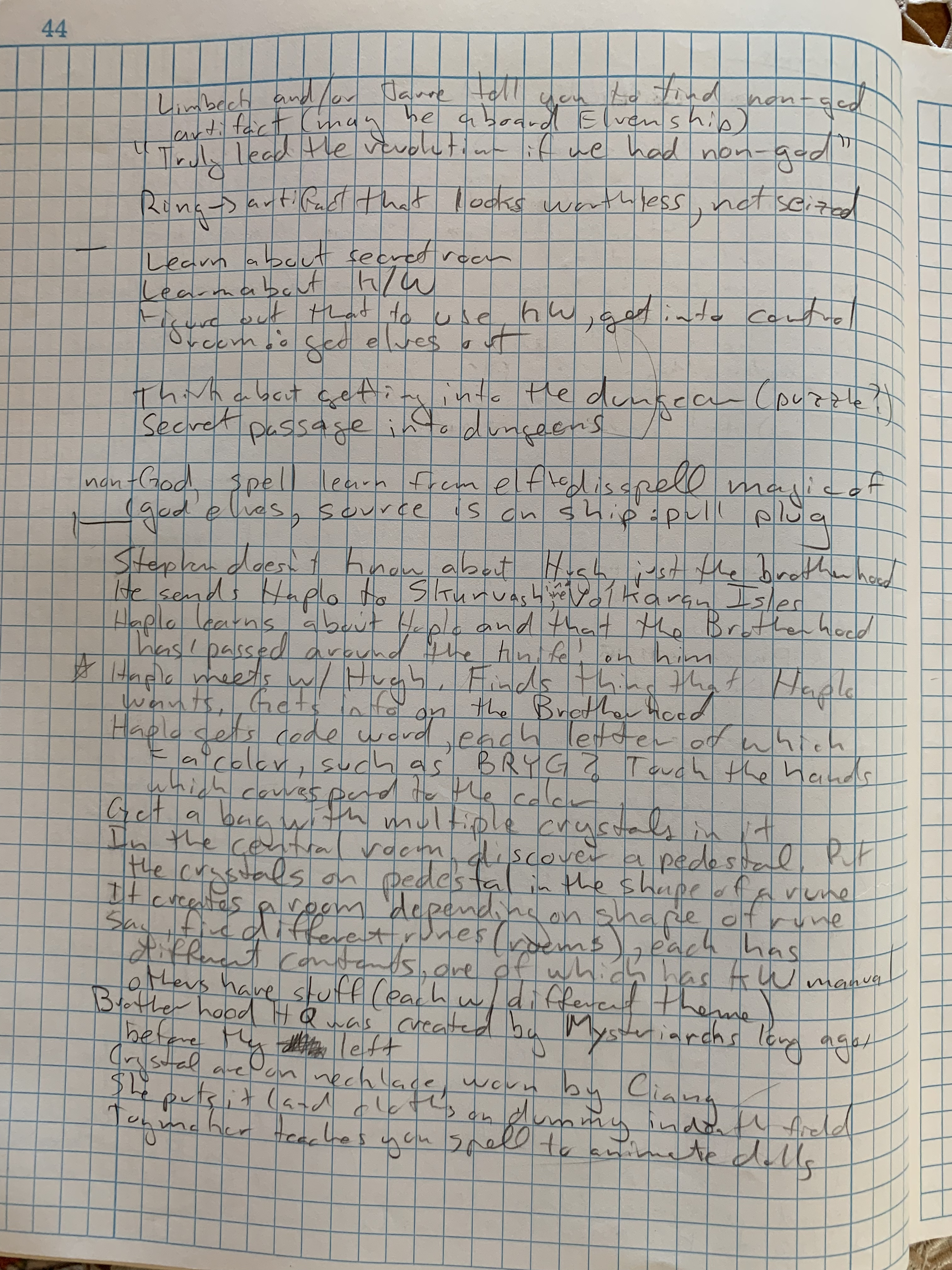

A Treasure from the Archives (My Notes)

Back in the old days, we didn’t have your new-fangled phones or tablets, or even laptops really. I kept all of my notes in an Engineering Notebook. Given that I rediscovered this recently, I figured it might be illuminating to reveal the design scribbles for Death Gate here. Keep in mind that it not only contains the actual design, but a lot of false starts or ideas that I might have not intended to use, but didn’t want to forget (including the entire section I dumped in Arianus). If you can decipher my handwriting and want to get a little insight into at least my design process for an adventure game, then you’re welcome to dive in.

Note that the first section is examination of the first four books and what I could use. Then I muse about the game in general and identify what I might pursue. Only later do I start detailing each section of the design in walkthrough form. When I finally generated walkthroughs, I was ready to code.

Normal people should feel free to skip all of this, but adventure game scholars: dig in!

The Reception

In most quarters, Death Gate was extremely well received. Readers of the book series acknowledged that the game was different than the source material, but still an excellent experience that was true to the spirit of the books. They enjoyed the logical puzzles, the excellent art, the fantastic music score mostly composed by Eric Heberling (with one song by me), and the compelling story born of an awesome and well-loved universe.

Death Gate won a number of awards, including the following:

- Computer Game Review’s Golden Triad Award

- InterActive Gaming’s Editor’s Choice Award

- Computer Gaming World’s Premier Finalist for Best Adventure Game 1995

- Strategy Plus Animated Adventure Game of the Year 1994 (runner-up).

Overall reviews were great. You can see a collection of them here on Mobygames. Of those, my personal favorite is the user review with the headline, “Were this game a spiky club, I’d take up masochism.”

I think that says it all.